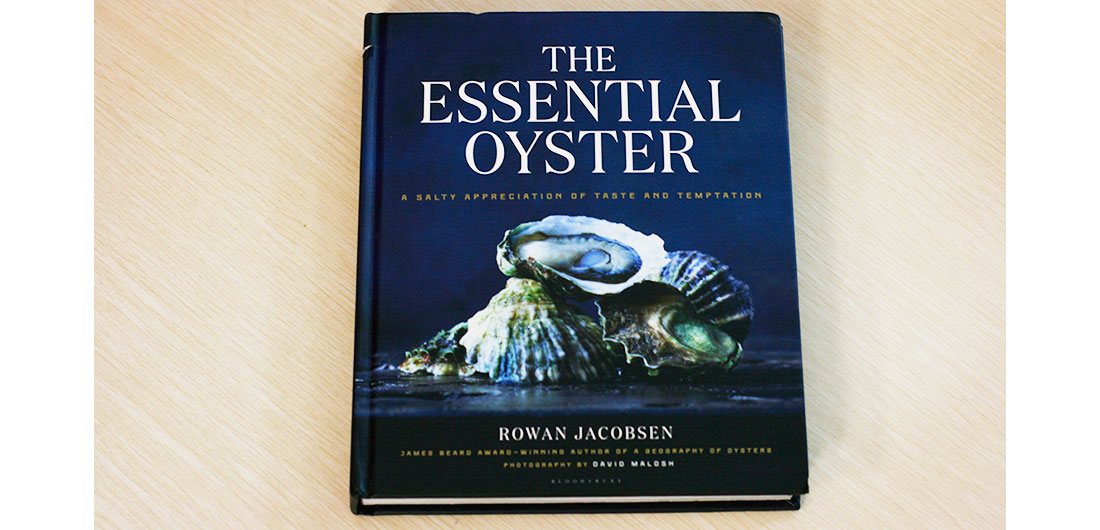

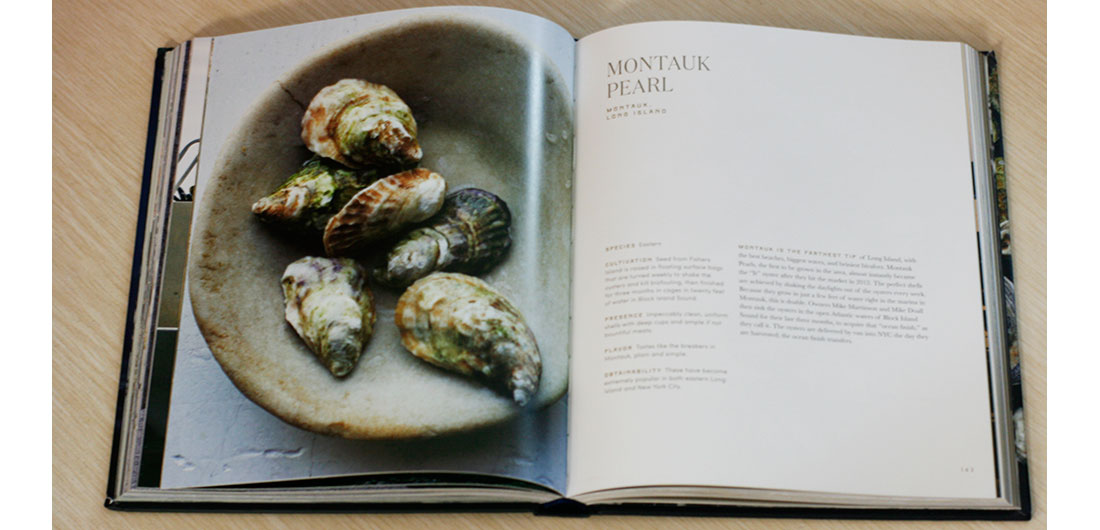

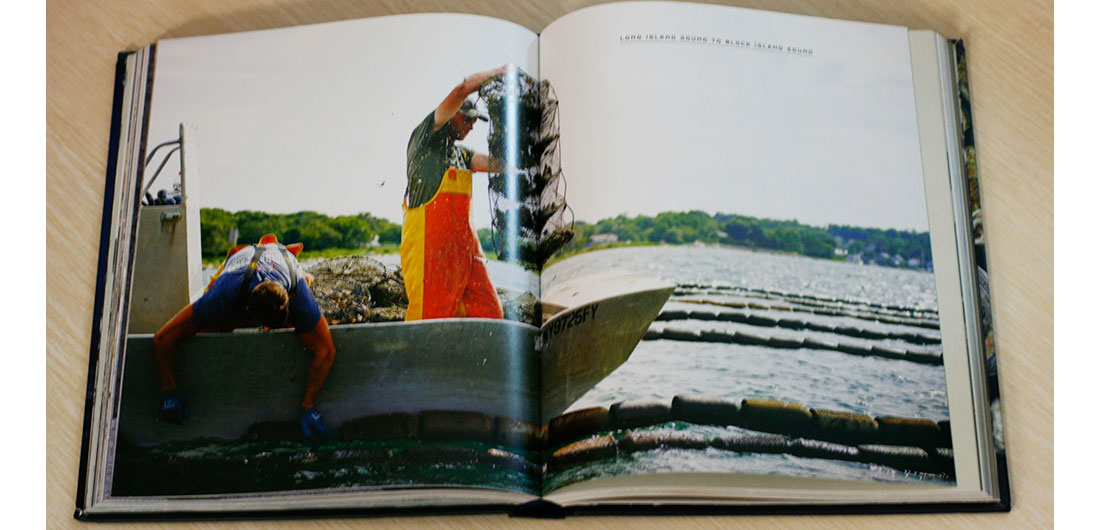

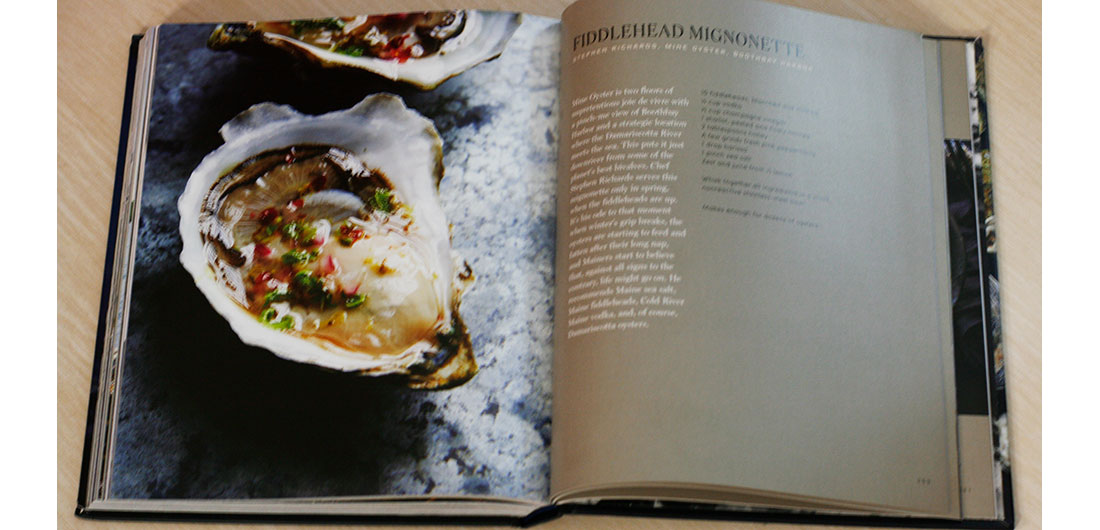

The Essential Oyster is out and available now, and it does NOT disappoint. With a blend of stunning photography (we helped contribute some oyster “models”) and poetic prose (is there any muse more inspirational than the sea?), this book is perfect for casual coffee table perusal or serious ostreaphile study. Best of all, far from being a dry dictionary, it captures the farmers and stories behind the oysters, transporting you from couch to Cape Cod in an instant.

Now, to answer the obvious question: Which of Jacobsen’s oyster books should I buy? Obviously, the ideal solution is to get both, but we understand that time and budget may not allow this. In that case, we recommend A Geography of Oysters if you’d like a deeper understanding of oysters through a more scientific approach (the book covers oyster species and aquaculture techniques well), and The Essential Oyster if you’d like to learn about the character of your oyster, truly a time capsule molded by history, creativity and idiosyncratic chance. Either way, you can’t go wrong.

Without further ado, here’s a few of my favorite moments from The Essential Oyster:

- Pacific oyster seed was imported from Japan, until the war interfered: By 1919, the native Olympia oyster beds had succumbed to overharvesting, and West Coast farmers turned to the fast-growing and disease-resistant Pacific oyster. It turned out to be cheaper to ship oyster seed from Japan, packed into wooden sake crates and sprayed twice a day with seawater, than to ship oysters from the East Coast. So, each year, one hundred thousand cases of seed were shipped to WA. This arrangement lasted until World War 2, when trade came to a halt for several years. At that point, oyster farmers began looking into ways to produce their own seed, and by the 1970s, West Coast hatcheries were in production to produce oyster seed for domestic use.

- European Flat oysters are being grown on the West Coast: I’m a long-time fan of the European Flat oyster (often sold as a “Belon“). For years, I’ve been telling people that these notoriously finicky oysters are difficult to cultivate, and in the US, the only place they flourish is in the Damariscotta River in Maine. Turns out I was wrong. There’s a farmer growing European Flats in Shoal Bay, off Lopez Island in Washington. Farmer Nick Jones not only has figured out how to grow these prima donnas, he is also running a geoduck farm, a fish brokerage, a sausage company, and raising wheat and barley on the side for distilling whiskey. Color me impressed.

- Green oysters are the new Holy Grail: Under the right conditions, oysters can turn a bright blue-green color, due to pigments produced by the blue diatom Haslea ostrearia. This may not be appealing for the average oyster eater, but the diatom is actually a powerful antioxidant and is also associated with excellent flavors in oysters. In fact, French oyster farmers actually add the diatom to their finishing ponds. In the US, green-gilled oysters are few and far between, but now there’s finally a wild harvester championing green oysters in North Carolina. This isn’t to say that the Atlantic Emerald oysters will be easy to find, but if you can get to the Outer Banks in winter and find a guy named Clammerhead who “looks like a biker, talks like a philosopher,” you might be poised for a real treat.

- Middens, evidence of a not-so-moveable feast: The Damariscotta River is fertile ground for oyster beds today, but it was an even more epic feast from about 2,500 to 1,000 years ago. How do we know? From the massive shell middens, hundreds of millions of shells deep, left on the banks of the river. Jacobsen writes, “All of a sudden, the western bank of the river changes from dirt and rock to pure-white shell hash. From the beach, the white cliff rises above you, and your mind struggles with numbers. Unfathomable abundance.” Even more interesting, you can see striations of other types of debris in the middens, which indicates that there were points where humans must have taken a break from harvesting oysters. Did we run out of oysters or simply run out of humans? Either way, it makes me want to start collecting and burying shells in my backyard for future anthropologists.

- You can be living in Paris, trading stocks, engaged to a count, and still become an oyster farmer: Abigail Carroll, the self-titled “Accidental Oyster Farmer” has one of the coolest stories of mid-life crisis, er, pivot I’ve ever heard. In 2008, she was living comfortably as a day trader, and dating a French count. Upon realizing that she didn’t actually want to become a countess, she returned to Maine and began working with a would-be oyster farmer. After she invested the capital for equipment and wrote a business plan for the farm, the other person left and Carroll was stuck with an oyster farm on her hands. She decided to simply become an oyster farmer herself, despite having no experience. Luckily, she had chosen a great oyster growing site. Nonesuch oysters are some of the best, and though Carroll’s life has taken some dramatic turns since her days in Paris, she is immensely happier now that she’s getting her hands dirty.

Have you had a chance to read one or both of these books? Let us know what you thought!