While we would love for all restaurant menus to give full descriptions of oysters, oftentimes the only information you get is the name of the oyster and the state that it’s from. Or, it may simply say “market selection,” which is even more uninformative. So, how do oyster names come about and what kind of information can we glean from them?

Traditionally, oysters were named after their location. Cotuit oysters were from Cotuit, MA, Wellfleet oysters were from Wellfleet, and so on. But if there were multiple oyster farmers from a particular town or bay, there would be no way of differentiating the oysters from each other, and no way to really compete except through lower pricing. Plus, unscrupulous farmers from outside that growing region could still sell their oysters under that name, since there’s no legal recourse to protect a geographic name.

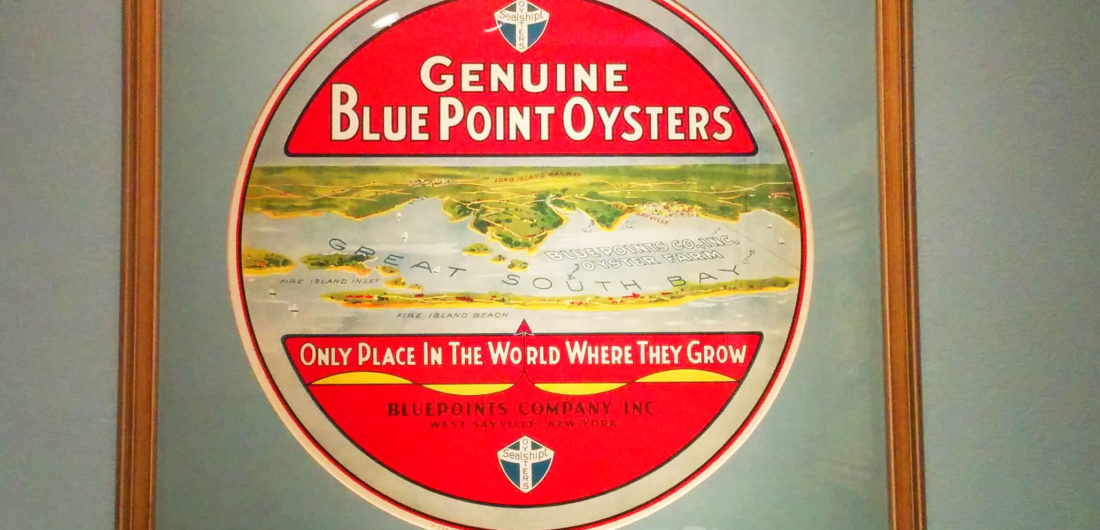

The Blue Point oyster fell victim to its own popularity in this way. Blue Point oysters originated from Blue Point, LI on the Great South Bay. In the early 1800s, they were renowned for their robust, wild flavor and became a favorite of Queen Victoria. The Blue Point name was so popular that people began pirating the name for any oyster from the Long Island Sound, New Jersey and beyond. Though the NY legislature passed a law in 1908 stating that Blue Point oysters must have been cultivated in the water of the Great South Bay, this was never really enforced, and a Blue Point became a generic term for any Long Island oyster. While you may be getting a great oyster, it’s likely not from Blue Point.

Hence, today’s farmers tend to create branded names for their oysters, something that ties the oyster to their operation, a name that is memorable and can be trademarked. The legal protections allow a farmer to promote their brand, and prevent anyone else from marketing their oyster under the same name. That’s great, right?

Well, it depends. Geographic location can give quite a bit of information for diners, so if a name doesn’t include the oyster’s origin and it’s not otherwise indicated on a menu, this can make ordering more difficult. This leads to diners choosing their oysters based on the name that sounds the “coolest” or most interesting, which is similar to choosing a wine based on the label art. Fun, but not that informative. On the other hand, if an oyster has a branded name that still includes its location (e.g. Montauk Pearl, Cape May Salt), you get the best of both worlds by knowing where the oyster is from and which farmer grew it.

One of our favorite oyster names is the Totten Inlet Virginica. If you unpack this name, you’ll know that the oyster comes from the West Coast (Totten Inlet is in WA), but that it is the East Coast species (Crassostrea virginica). What a novelty; the eastern oyster species grown on the West Coast! You’ll already know what to expect for the shell shape and meat, and perhaps even a little of the flavor.